Crop resistance

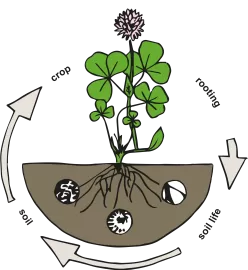

Soil resistance ensures that crops do not suffer from disease as soon as a pathogen occurs in the soil. Soil resistance is enhanced by biological activity in the soil, but also by the availability of the right minerals.

Biological resistance is created by the 'beneficial' soil life competing with pathogens for nutrients and space. Bacteria and fungi that are near the plant root digest the substances excreted by the root. The root exudates are quickly converted, which means pathogenic fungi do not have a chance to germinate. The physical room on and around the roots also plays an important role. If this room is fully occupied by beneficial organisms, the pathogen has no room for further development. Some beneficial fungi grow in the root itself, which means they protect the root against undesirable penetrants.

Specific groups of organisms can strengthen the biological resistance of the soil. For example fungi that catch nematodes, that live on pathogenic nematodes or predatory nematodes that need other nematodes as a source of food. There are beneficial organisms that excrete substances, such as antibiotics, and in doing so help to remove the pathogen. There are also large groups of organisms in the soil that excrete enzymes to their environment. Difficult to absorb organic compounds are decomposed and made suitable for digestion. These enzymes can also affect pathogenic fungi or nematodes.

The chemical properties of the soil play a role in the disease resistance of the soil. Pathogens, organisms that cause disease, can be encouraged or stopped by the pH value of the soil. Trace elements have a positive effect as beneficial organisms are often better able to absorb trace elements than pathogens. Finally, the physical components can affect soil resistance. An example is a poor soil structure that can cause surplus water, which means certain pathogens can be spread.